- 3 4 Inch Margins Microsoft Word Free

- One Inch Margins Microsoft Word

- 3/4 Inch Margins In Word

- 3 4 Inch Margins Microsoft Word Download

Most greeting card sizes are about 5 x 7 inches with an A7 (5.25 x 7.25-inch) envelope; about 4.5 x 6.125 inches (or 4 x 6 inches) with an A6 (4.75 x 6.5 inches) envelope; or 4.25 x 5.5 inches. Microsoft Word offers several page margin options. You can use the default page margins or specify your own. Add margins for binding A gutter margin adds extra space to the side margin, top margin, or inside margins of a document that you plan to bind to help ensure that text isn't obscured by binding. Gutter margins for binding.

Главная > Документ

Смотреть полностью

Jul 04, 2018 3 4 inch margins microsoft word. 7/4/2018 0 Comments To change the peak margin to 1 12 inch, select the current setting and then type 1. 5 or you can click the arrows. Note that Word 2010 will only allow two decimal places for margins, however, so you would need to use 1.18 inches if you wanted 3 centimeter margins, or.79 inches if you wanted 2 centimeter margins. How to insert a check mark in Microsoft Word; How to do small caps in Microsoft Word; How to center text in Microsoft Word.

[Toformat, set margins to one inch and font to Courier New, 10 points]

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

ParkScience

IntegratingResearch and Resource Management

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Volume20 –- Number 2 -– Fall / Winter 2000 (ISSN–0735–9462)

www.nature.nps.gov/parksci

= = = Masthead = = = = =

<i>Publishedby</I>

U.S.Department of the Interior

NationalPark Service

RobertStanton, Director

MichaelSoukup, Associate Director, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science

<i>Editor</i>

JeffSelleck

<i>Contributors</i>

InformationCrossfile -- Elizabeth Rockwell

Highlights-- Jennifer Gibson, Sherry Middlemis-Brown

News& Views -- Rook Cleary

<i>Design</i>

GlendaHeronema

<i>EditorialBoard</i>

*Ron Hiebert (chair)--Research Coordinator, Colorado Plateau CESU

*Gary E. Davis--Science Advisor and Marine Biologist; Channel IslandsNP

*John Dennis--Biologist, Natural Systems Management Office

*Jared Ficker--Social Science Specialist, NPS Social Science Program

*Rich Gregory--Chief, Natural Resource Information Division

*William Supernaugh--Superintendent, Badlands NP

*Judy Visty--Fall River District Interpreter, Rocky Mountain NP

*Vacant--Park Chief of Resource Management

<i>EditorialOffice</i>

NationalPark Service

WASO-NRID

P.O.Box 25287

Denver,CO 80225-0287

E-mail:jeff_selleck@nps.gov

3 4 Inch Margins Microsoft Word Free

Phone:303-969-2147

FAX:303-969-2822

<i>ParkScience</i> is a resource management bulletin of the NationalPark Service that reports recent and ongoing natural and socialscience research, its implications for park planning and management,and its application in resource management. Published by the NaturalResource Information Division of the Natural Resource Program Center,it appears twice annually, usually in the spring and summer.Additional issues, including thematic issues that explore a topic indepth, are published on occasion. Content receives editorial reviewfor usefulness, basic scientific soundness, clarity, completeness,and policy considerations; materials do not undergo anonymous peerreview. Letters that address the scientific content or factual natureof an article are welcome; they may be edited for length, clarity,and tone. Mention of trade names or commercial products does notconstitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National ParkService.

Sendarticles, comments, address changes, and other information to theeditor at the e-mail address above; hard copy materials should beforwarded to the editorial office address. Deadline for submissionsis January 15 for the spring issue and April 15 for summer.

<i>ParkScience</i> is also published on-line (ISSN-1090-9966). Allback issues of the publication, article submission guidelines, andother useful information can be viewed and downloaded from thewebsite www.nature.nps.gov/parksci.

<i>ParkScience</i> accepts subscription donations from non-NPSreaders. If you would like to help defray production costs, pleaseconsider donating $10 per subscription per year. Checks should bemade payable to the National Park Service and sent to the editor.

<i>Samplearticle citation</i>

Oelfke,J. G., and R. G. Wright. 2000. How long do we keep handling wolves inthe Isle Royale wilderness? [National Park Service publication] ParkScience 20(2):14-18.

= = = Contents = = = = =

<b>Departments</b>

(1) From the Editor

(2) News & Views

(3) Highlights

(4) Information Crossfile

(5) Book Review

(6) Meetings of Interest

<b>CoverStory</b>

(7) How long do we keep handling wolves in the Isle Royale wilderness?

<i>Anexpert panel examines the difficult resource management question inconsideration of wilderness values and the advantages of particularscientific information obtained through monitoring.</i>

ByJack G. Oelfke and R. Gerry Wright

<b>Features</b>

(8) A conversation with Point Reyes Superintendent Don Neubacher

<i>Thenational seashore leader discusses the use of science in parkmanagement, the Natural Resource Challenge, and the future ofresource preservation at the California coastal park. </i>

Bythe editor

(9) Protecting resources and visitor opportunities: A decision processto help managers maintain the quality of park resources and visitorexperiences

<i>Researchersfacilitate and study the use of the timely process in field testsconducted at Mesa Verde, Yellowstone, and Arches. </i>

ByTheresa L. Wang, Dorothy H. Anderson, and David W. Lime

(10) Late Jurassic (Morrison Formation) continental trace fossils fromCurecanti National Recreation Area, Colorado

Theauthors describe an alternative to removing fossils from a park fortheir preservation, study, and educational use. </i>

ByAnthony R. Fiorillo and Richard L. Harris

(11) An Importance-Performance evaluation of selected programs in theNational Center for Recreation and Conservation

<i>Researchersassess satisfaction among cooperators who received assistance orservices from four NPS programs: Rivers, Trails, and ConservationAssistance; National Heritage Areas; Federal Lands-to-Parks; and Wildand Scenic Rivers.</i>

ByMichael A. Schuett, Steven J. Hollenhorst, Steven A. Whisman, andRobert M. Campellone

<b>Onthe cover</b>

Wolvestravel the icy shoreline of Siskiwit Bay at Isle Royale NationalPark, Michigan. After having suuccessfuully stuudied wolves and mooseon this wilderness island for 3 30 years without handling, biologistsbegan a live-trapping program in 1 1988 that provided importantgenetic information to managers. Last year the park investigated thepossibility of returning to a hands-off monitoring approach.

Photoby Rolf O. Peterson

(1)= = = = = From the Editor = = = = =</i>

<b>Restylingin the century of the environment</b>

Nearlysix years have elapsed since the last face-lift given to </i>ParkScience.</i> The current changes coincide with the newmillennium, or what participants to Discovery 2000 last September inSt. Louis began referring to as the “century of the environment.”The purpose of the changes, however, is based on a practical matterrather than a symbolic one: to compel the interest of new readers,both within and outside the National Park Service, and to stimulategreater appreciation for science-based park management.

Aboutto begin its 21st year, </i>Park Science</i> has adevoted audience. Yet we have often wondered who is not reading itand what we could do to induce them to become readers. We even askeda question to this effect in a reader survey five years ago, and wegot a few varied responses. Among them were to include more socialscience articles, feature the recommendations of superintendents,upgrade the science being reported, print both technical andnontechnical articles, provide more information on potential grantsources, help build synergy between maintenance and resourcemanagement operations, provide real-world management solutions, andpublish on the Web. In many cases we have acted upon these ideas. Onesuggestion, however, has not been addressed until now: to make thispublication more competitive with the many newsletters and bulletinsthat vie for the attention of readers.

Withimpetus from the <i>Park Science</i> editorial board anddesign concepts provided by Glenda Heronema of the Denver ServiceCenter, we introduce a new look for <i>Park Science</i>this issue that is more attractive and magazine-like, and thus morefriendly and inviting. Gone is the institutional newsletterappearance, replaced by more fully developed pages and the use ofcolor as an enticement to new recruits and devoted readers alike. Wesincerely hope the new design will garner attention from thoseotherwise inclined to pass it by, while retaining the interest ofthose who have always found it informative. We believe the new lookwill broaden our reach, increase our ability to nurture science-basedpark management, and build public awareness and understanding of ourresource preservation mission. Please let us know what you think.

Doesthis signal a change in our message? Essentially, no. </i>ParkScience</i> will continue to report recent and ongoing researchand its application in park management. However, as we begin thiscentury of the environment, we want to be more inclusive of all parkoperations and plan to modify the Highlights department along theselines. Specifically, we want to feature brief articles that describewhat all NPS operations in parks are doing to preserve naturalresources and how they are applying science to improve their ownoperations.

Forexample, we want to share the contributions of maintenance andvisitor and resource protection divisions to the accomplishment ofnatural resource management projects. Likewise, interpretive programsthat involve the public and school children in our natural resourcemanagement programs through hands-on participation are of interest.We want to feature the views of park superintendents on the role ofscience in resolving management problems. And, of course, we intendto continue publishing research results that have implications fornatural resource management along with reports of the many activitiesof park natural resource programs across the nation.

Asalways, we invite you to participate in </i>Park Science</i>by submitting your stories and helping us achieve this goal.

JeffSelleck

Editor

(2)= = = = News and Views = = = = =

AlcatrazBird Census

DearEditor,

Thearticle entitled “Alcatraz bird census … or the ABC program” inthe spring 2000 issue of <i>Park Science</i> [20(1):6]contains several inaccuracies. Ranger Brett Woods did found theAlcatraz Bird Census (ABC) in the early 1990s. However, after hisbrief stint on the island ended, I took over ABC program management.The program hardly “languished” as the article stated. Instead,it ran successfully until I left the island in 1997.

Iworked on Alcatraz from 1991 to 1997. Among my myriad duties, Iserved as Natural Resources Coordinator for the island. I recruited,trained, and supervised the volunteers that conducted the ABC until Ileft for Everglades National Park in 1997. During my tenure as“Birdman of Alcatraz,” the ABC did quite well. There was noapparent need for changing the census procedures or databasemanagement. I was therefore disturbed to note that the articlesuggested that the ABC stagnated or stopped after Woods’ departure.

<i>WilfredoReyes

ParkRanger

EvergladesNational Park

GoldenGate NRA regrets the article’s tone. However, the decision tostandardize methods for recording bird frequency and occurrence dataon Alcatraz along with regular reporting has improved the value ofthe information. For example, the area search protocol <sup>1</sup>, now used on Alcatraz and at other areas in the park, distinguishesbirds on land from those on water, information that was useful topark management in a recent environmental impact statement. Thetechnique has other benefits, including its widespread usage.Database management evolved to reflect the needs of the protocol, andthe software was changed to meet the NPS standard. </i>

[Footnote]<sup>1</sup> Ralph, C. J., G. R. Geupel, P. Pyle, T. E.Martin, and D. F. DeSante. 1993. Handbook of field methods formonitoring landbirds. USDA Forest Service, Publication PSW-GTR-144,Albany, CA.

** *

Axtelland Vequist take on new challenges

Lastspring, Mike Soukup, the Associate Director for Natural ResourceStewardship and Science, announced the selection of Craig Axtell asChief of the new Biological Resource Management Division.Headquartered in Fort Collins, the new division will help carry outthe thrusts of the Natural Resource Challenge to protect native andendangered species and their habitats and to aggressively controlnonnative species. The division was funded and established in FY2000.

Intaking the new position, Axtell left his job with Rocky MountainNational Park where he served as Chief of the Division of ResourceManagement and Research. His career with the National Park Servicespans 25 years and also includes positions as Park Planner andEconomist with the Denver Service Center and Resource ManagementSpecialist at Everglades and Isle Royale National Parks. He graduatedfrom Colorado State University with a B.S. in forest science and anM.S. in natural resources management.

Sincecoming on board in May, Axtell has been busy setting up Exotic PlantManagement Teams to address the problem of invasive plants in parks.Four teams are currently operational and have begun exotic planteradication efforts at parks in the National Capital Region,Chihuahuan Desert and shortgrass prairie, Hawaiian Islands, andFlorida. Other functions of the new division are nationalcoordination of threatened and endangered species management,integrated pest management, technical assistance with animal trappingand wildlife veterinary operations in parks, and advice to parks onother complex biological resource issues.

Alsomaking a switch in jobs is Gary Vequist, who was recently selected asthe Associate Regional Director for Natural Resource Stewardship andScience in the 13-state Midwest Region. Duty stationed in Omaha,Nebraska, Vequist formerly served as Chief, Resource Management andVisitor Protection, at Carlsbad Caverns National Park in New Mexico.He replaces Ron Hiebert, who transferred to the Colorado PlateauCooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit at Northern Arizona University inFlagstaff, Arizona, last December.

Beforehis assignment at Carlsbad, Vequist held positions as the AlaskaRegional Resource Manager for seven years and supervisory resourcemanager at Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska, for eight years, inaddition to numerous other seasonal park positions. He earned a B.S.in zoology from Washington State University and an M.S. inenvironmental quality engineering from the University of Alaska. Hebrings to his position broad experience working with speciesinventorying and monitoring, fire and cave management, visitorprotection programs, and scientific research.

** *

Ecosystemvaluation website launched

One Inch Margins Microsoft Word

Areyou looking for ways to increase the relevance of your park’sresource preservation goals and projects in the eyes of parkvisitors, neighbors, and other constituents? While justifying suchprograms and actions strictly on economics would be folly, economicsshould not be ignored and can help managers evaluate whichpreservation projects to undertake and how to justify their expense.Resource managers may find the website “Ecosystem Valuation”helpful in understanding how economists value the beneficial waysthat ecosystems affect people. Written and developed by Dennis King(University of Maryland) and Marisa Mazzotta (Univeristy of RhodeIsland), the site is designed for non-economists who need answersabout the benefits of ecosystem conservation, preservation, orrestoration. It provides a clear, nontechnical explanation ofecosystem valuation concepts, methods, and applications.

Thewebsite contains: a discussion of the purposes and context forecosystem valuation (The Big Picture); a nontechnical overview of theeconomic theory of benefit estimation (Essentials of EcosystemValuation); descriptions of specific valuation methods, includingboth dollar-based measures and nonmonetary measures (Dollar-BasedEcosystem Valuation Methods, and Ecosystem Benefit Indicators); casestudy illustrations of each method; practical considerations relatedto the methods, including when each method is most appropriate, andthe links to sources of related information (Links); andopportunities to provide feedback and share your experiences as youdevelop and use estimates of ecosystem benefits (Feedback).

TheURL for Ecosystem Valuation is /. The siteis funded by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and theNational Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

(3)= = = = = Highlights = = = = =

Studentsgather data at Sitka

[Threephotos] Students weigh and sample juvenile fish at Sitka NationalHistorical Park, Alaska, as part of a Nature Watch Program toencourage hands-on experience in scientific monitoring and naturediscovery. One student improved the park herbarium, adding 18 speciesof seaweed, including the one at the right, as voucher specimens.

SitkaNational Historical Park is located at the mouth of Indian River,which flows through a temperate rainforest in southeastern Alaska. InSeptember 1999, the park started a Nature Watch Program to givemiddle school and high school students hands-on experience inscientific monitoring and the discovery of nature. Local students andthose attending boarding school from remote villages are documentingthe state of local watersheds through stream surveys, biologicalinventories, water chemistry analysis, measuring stream flows,recording types of streambed materials, identifying juvenile fish,and mapping river channels. Students collect these data with helpfrom park biologist Jennifer Williams, park rangers, and volunteersfrom Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G), U.S. ForestService, and the Sitka Tribe of Alaska.

Oneof the program activities, fish surveys, was conducted throughout theyear and provided the students with a valuable hands-on experience infish identification and handling, data collection, and projectorganization. The goal of these surveys was to determine the speciespresent and their age class. First, the students learned todistinguish between juvenile coho salmon and Dolly Varden, then theyseparated the species into designated buckets. If a fish species wasunknown to the student, the ADF&G or NPS biologist helped makethe identification. Next, three students weighed and measured thejuvenile fish and recorded the information. The information will beused to determine how long the fry develop in the stream beforemigrating to sea.

Theprogram, which ran through last winter, created a new source of datafor park managers. The students’ fish sampling efforts haveresulted in documenting the presence of cutthroat trout, a speciespreviously unknown to raise its young in Indian River. Sampling ofjuvenile fish is also helping the park delineate prime rearinglocations for salmon, trout, and char. The information collected willbe used to better understand and protect park resources.

SashaStortz, a 10th grader, found the park’s resources interestingenough to volunteer time throughout the summer. Working on a vouchercollection project, Sasha has pressed and added 18 new species ofseaweed to the park’s current herbarium of 50 species. Later insummer she assisted with production of Web page photo galleriesspecific to the natural resources at Sitka National Historical Park.

SitkaNational Historical Park’s Nature Watch Program has brought thepark closer to the community, raised awareness of park resources,allowed students to discover more about nature, and offered creativeopportunities for individual students. The park will continue toenhance the program through future proposals and community outreach.

** *

GaugingHoover’s fishing hole

Floodsand stream flow form the basis of a partnership between HerbertHoover National Historic Site (Iowa) and the Iowa District of theU.S. Geological Survey (USGS). After flooding in 1993, the USGSassessed flood recurrence on a tributary of the west branch of theWapsinonoc Creek within the park. The USGS has continued itsrelationship with Herbert Hoover National Historic Site since thattime by installing a National Streamflow Network stage gauge in thepark.

TheNational Streamflow Network of the USGS consists of more than 7,000gages across the nation. These gauges contribute the data necessaryto address water quality and quantity issues. Data appear on the Webat gs.gov.

HerbertHoover National Historic Site uses the gauge as part of a watermonitoring program. Flooding poses a threat to historic resources inthe park with a high probability that a 25-year recurrence floodwould cause damage to structures. Understanding the behavior of thecreek may lead to better prediction and mitigation of damagingfloods.

Thepark also uses the gauge as a demonstration of natural resourcemanagement. Interpretive signs and a digital readout of real-timedata accompany the gauge housing in a high traffic area of the park.Visitors can

readmeasurements of water temperature, air temperature,

rainfall,and stream flow.

Parkstaff use the stream to help visitors understand that humandevelopment has changed water resources in the last two centuries.Wapsinonoc Creek, and its tributary in the park, were very differentstreams when President Hoover fished them as a boy. Riparian wetlandsstabilized stream flow, but development encroached on these wetlandsat the turn of the century. Field tiling and additions of impermeablesurfaces within the watershed increased the rate and quantity ofrunoff from storm events. These changes have resulted in flashflooding and bank erosion on the creek.

Thestream gauge provides an opportunity to use resource managementissues in the park to deliver a broad message about watershedprotection and land use. The gauge will provide data for managementdecisions concerning land use and cultural landscape within the park.Additionally, it will provide the National Park Service with hardscience for its leadership role as a public land and watershedsteward.

** *

Articleswanted

Doyou have a story you want to see published in Highlights or anotherdepartment of <i>Park Science?</i> All you need to do isshow how a park operation such as resource management,interpretation, visitor and resource protection, or facilitymanagement is contributing to the preservation of natural resourcesin a unit of the national park system through the application ofscience. Send your submission to the editor (see back cover forcontact information) along with a photograph to illustrate your mainpoint. More complete guidelines for submitting all types of articlesfor publication are available on the <i>Park Science?</i>website (www.nature.nps.gov/parksci).

(4)= = = = = Information Crossfile = = = = =

Visitors,ungulate management, and interpretation

Managementof ungulates in the national park system has varied throughout thehistory of the parks. From 1900–30 attempts were made to increasenumbers of ungulates and enhance viewing opportunities. Concern aboutthe overabundance of ungulates was prevalent from 1930–40 and in1941 through 1968 parks instituted control programs to limit ungulatenumbers. Since 1970, when activist citizen groups emerged, publicinvolvement in environmental decisions increased drastically. Becausethey want to view animals and preferably at close range, visitorshave an interest in the management and welfare of wildlife in parks.

However,surveys revealed that the American public has a poor understanding ofecological concepts and therefore as difficulty in the comprehensionof resource management in parks. Examples are the opposition of thepublic to removal of the mountain goat from Olympic National Park(see photos) where this species is considered alien and thediscontinued removal of exotic burros from the Grand Canyon.

[photosof mountain goats in Olympic National Park, Washington]

R.G. Wright, writing in the Wildlife Society Bulletin (1998. A reviewof the relationships between visitors and ungulates in nationalparks. No. 26(3):471–76), suggests that interpretive programs inparks could play a more important role in educating the public aboutsound park-specific management of ungulates. Park interpretiveprograms could be strengthened if they regularly included (1)explanations of the effects of land use adjacent to a park on thepark and its wildlife, particularly migratory species; (2)explanations of the environmental, cultural, or ecological functionof resource management; and (3) briefings on and explanations ofimpending management such as control of alien species or culling ofoverabundant animals.

Meetingthe public’s desire to see wildlife in parks without creatingdisturbance of the animals and without inviting well-meaning butinappropriate reversal of management is challenging and calls forinnovative techniques. Because of budget limitations and fears ofvisitor dissatisfaction, some parks seem reluctant, for example, tohave visitors leave their vehicles and use public transportation toreduce disturbances of wildlife but increase viewing. (An exceptionis Denali National Park, which tightly controls private vehicle useon a 130-km road; most visitors use public transportation.) Wrightsuggests that increasing public understanding of wildlife managementin parks may be the only alternative of meeting the objectives ofprotecting wildlife in parks and retaining the support of the public.Visitors must be made to understand that parks were established assanctuaries where animals can live in nature but are not to be placedon display, and that management of a park must be toward that end.

** *

Wildernessmanagement survey

Avariety of programs designed to foster personal development ortreatment of various ailments offer wilderness experience to payingclients. The programs are held in designated units of the NationalWilderness Preservation System and on other public or private landsthat offer naturalness and solitude. The excursions have socialbenefits for the clients but may pose a threat to the very wildernessthat inspired them.

Preventingadverse effects by wilderness programs is already a grave concern inmany areas, but information about such effects was not availableuntil four investigators began a study and collected data about theattitudes, policies, and concerns of wilderness area managers (Gager,D., J. C. Hendee, M. Kinziger, and E. Krumpe. 1998. What managers aresaying—and doing—about wilderness experience programs. Journal ofForestry 96[8]:33–37). The researchers sent eight-pagequestionnaires about policies, attitudes, concerns, and preferredsolutions of problems to the supervising administrators of 151 unitsin the National Wilderness Preservation System: 78 national forests,49 units in the National Park System, 6 BLM state jurisdictions, and18 national wildlife refuges. They excluded islands and areas smallerthan 5,000 acres where overnight use by wilderness experienceprograms was unlikely. They received responses about 144 (95%) units.

Two-thirdsof the mangers felt that the use of wilderness in their areas ofresponsibility was increasing. More than a third thought use wasgrowing 25 percent per year or more. All the agencies requiredpermits for use by wilderness programs. Almost a third (29%) of themanagers felt that their agency policy was not sufficientlyrestrictive; most (67%) thought theirs was just right; some (4%)thought theirs was too restrictive. Managers in the USDA ForestService and the National Park Service tended to think their agencypolicies were not sufficiently restrictive. Bureau of Land Managementand U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service managers thought their policieswere just right. As many as 31 percent of the managers suggested thattheir current policies were too ambiguous or incomplete or that theydid not know enough about the number or types of wilderness programsusing their areas. Another third reported that their policies eitherwere under revision to be made more restrictive or wished theirpolicies would be revised.

Thegravest reported problems created by wilderness experience programswere establishment of new trails and sites, overuse in alreadysaturated areas, site impacts, large group size, lack of wildernessstewardship skills and knowledge, and conflicts with other recreationusers. Managers favor programs that promoted understanding and caringfor the wilderness resource over programs that emphasized challenge,adventure, and personal growth. Almost a third of the managers thinkthe programs conflicts with other users. Managers want higherstandards and better compliance with regulations, certification ofprogram leaders, and liability insurance. Managers recognize thebenefits of the program to the participants but do not think that theprograms are wilderness dependent.

Thesurvey revealed that communication and coordination among agencymanagers and wilderness experience program leaders are needed toavoid misperceptions and differences, and minimize the adverseeffects by the programs, namely, to secure the benefits of wildernessfor present and future generations.

** *

Selectingbiological indicators for resource monitoring

Heavyvisitor use in parks can cause unacceptable deterioration ofresources such as soil compaction, soil loss, vegetation loss,disruption of normal nutrient cycles, changes in hydrologic cycles,and changes in animal populations. To identify biological indicatorsthat measure visitor effect and response of resources to management,Arches National Park developed a Visitor Experience and ResourceProtection (VERP) plan that prescribes five steps (Belnap, J. 1998.Choosing indicators of natural resource condition: A case study inArches National Park, Utah, USA. Environmental Management22[4]:635–42). (1) Identified are vegetation types that visitorsuse most. Compared are samples of vegetation and soil in affected andunaffected sites. (2) Variables that differ significantly between thecompared sites are used as potential indicators. (3) Site-specificcriteria for indicators are developed with information from previousstudies and local experience, and potential indicators are evaluatedwith the criteria. (4) The selected indicators are further examinedfor ecological relevance. (5) Final indicators are selected andfield-tested, and monitoring sites are designated.

Indicatorsfor monitoring annually in Arches National Park were a soil crustindex, soil compaction, and the number of used social trails and soilaggregate stability. Indicators for monitoring every five years werevegetation cover and frequency, ground cover, soil chemistry, andplant tissue chemistry. For monitoring, Arches National Park wasdivided into zones that reflect various types and levels of visitoruse. In these zones, sites that were affected most by visitors weremonitored under the assumption that these sites would best indicatecompliance in the rest of the zone. Monitoring sites were changedwith changes in visitor use.

Theapproach to indicator selection in Arches National Park was time- andcost-effective. The identified indicators were better than geneticindicators for different habitat types, geographical locations, oruse levels. The process was effective for defining acceptableresource conditions for different levels and types of recreation andfor providing management with clear, quantified directions.Weaknesses of a plan like VERP are (1) the need for lead time (2years or longer) to survey habitats, develop a list of potentialindicators, determine ecological relevance, and field-test theindicators; (2) staff expertise for the assessments; and (3) time andmoney, constraints of which may necessitate that measured variablesare limited to those that are clearly visible, inexpensive, and easyto measure. The tiered approach of measuring some variables annuallyand other variables less frequently may be an acceptable response totime and money constraints.

** *

Globalwarming favors invasive species

Elementsof global change include change in atmospheric composition,greenhouse-gas-driven climate change, increasing nitrogen deposition,and changing patterns of land use that fragment habitats and alterdisturbance regimes (Dukes, J. S., and H. A. Mooney. 1999. Doesglobal change increase the success of biological invaders? Tree14[4]:135–39). These elements can affect species distribution andresource dynamics in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. They canfavor groups of species that share certain physiological or lifehistory traits. New evidence suggests that many nonnative invasivespecies are favored by conditions from recent global change. Anincrease in the abundance of such species may alter basic ecosystemproperties. For example, many invasive nonnative plants such ascheatgrass, kudzu, and Japanese honeysuckle are favored by elevatedlevels of CO 2. The stimulated plant growth from elevated levels ofCO 2 may increase fuel loading and under the right conditionsincrease the frequency and severity of fires. Information fromexperimental studies suggests that rising CO 2 levels may slow theprocess of succession in grasslands and thereby increase thedominance of nonnative species in many ecosystems. Most plantsincrease their water-use efficiency if grown in CO 2-enrichedenvironments. If under such circumstances the rate at which plantstranspire decreases, the soil beneath plants dries out more slowlyand where plant growth is limited by water, species that can takeadvantage of the extra moisture may eventually prevail. The abundanceof a native species, Hayfield tarweed, in California seems to haveincreased from such circumstance. But so did seemingly the invasiveyellow starthistle. The effects of elevated CO 2 levels are howevernot readily predictable because they may depend on other factors suchas local resource availability, photosynthetic pathways of species,and competition by other species.

Globalwarming from greenhouse gases is expected to be most intense inwinter at high northern latitudes. Changes in global temperatures arealso expected to change precipitation regimes. Again, experimentsrevealed that under some circumstances a short-term increase in wateravailability can affect the long-term establishment of nonnativespecies even after treatments are discontinued. Long-termobservations revealed that an increase in annual precipitation inarid and semiarid regions of western North America could increase thedominance of invasive nonnative grasses. On the other hand, globalwarming may decrease or shift the range of some nonnative species.

Observationssuggest that climate change will affect interactions among native andnonnative animal species. For example, higher temperatures will favorthe Argentine ant to the detriment of native ant species and willdecrease habitat for cold, cool, and even some warm-water species.Warm-water nonnative organisms that may expand their ranges are thecane toad, largemouth bass, green sunfish, and bluegill. Generaliststhat unlike specialists do not depend on specific conditions willadjust better to changing environmental conditions. Invasive speciesare usually generalists.

Nitrogenouscompounds that are released into the atmosphere by fossil fuelcombustion, fertilization of agricultural fields, and other humanactivities return to the surface in precipitation and dry depositionand fertilize a large and growing portion of the terrestrialbiosphere. Such nitrogen deposition disadvantages slow-growing nativeplants that are adapted to nutrient-poor soils but favors fastergrowing plants such as grasses. The increase of nitrogen depositionhas already altered the species composition of heathlands and chalkgrasslands in the Netherlands. Nitrogen deposition may also havealready allowed the invasion of California coastal prairie byintroduced annual grasses.

Researchis required to better predict the effects of global climate change onplants and animals. Experiments must be designed that simultaneouslyreveal the effects of global change on specific nonnative species andanswer general questions about invasion biology.

(5)= = = = = Book Review = = = = =

EcologicalScale--Theory and Applications

ByD. L. Peterson and V. Thomas Parker, editors

Abook review by Allan F. O’Connell, Jr.

Muchof how we care for and manage our natural world this century willrevolve around how ecological scale is interpreted. The question ofscale—the range of specificity applied in natural resource studiesand management—is fundamental and critical for ecologists. Yetapplication of scale concepts is a complex and contentious area ofecology that is often difficult for resource managers to implement inplanning and conservation efforts. Given the enormous amount ofmaterial currently available and the difficulty scientists andresource managers face in simply finding all available literature ona particular topic, “Ecological Scale—Theory and Applications”represents an important compilation of information under one cover.For a topic described as “important, poorly understood, andcontroversial” (another review of this book), this publicationshould be a mainstay for scientists and resource managers everywherein need of a thorough and first-rate reference on ecology.

Partof the “Complexity in Ecological Systems” series, EcologicalScale is divided into four sections: (1) integration of process,pattern, and scale; (2) interpretation of multiple scales inecosystems; (3) ecological inference and application—moving acrossmultiple scales; and (4) incorporating scale concepts in ecologicalapplication. The entire volume is 608 pages, with 33 differentcontributors (some authors participated in more than one chapter) and72 pages of references. The book is truly interdisciplinary, and theeditors have clarified and illuminated the importance of scale in avariety of ecosystem components: animals (including an entire chapteron large mobile organisms), plants, water, food webs, and soils.Additional highlights include scale-oriented reviews of ecologicaltheory, ecosystem management, relationships to policy and decisionmaking, experimental design, and measuring environmental change.

Aprevious book review in <i>Park Science</i> stated “manybooks on conservation topics have poorly integrated chapters, arehard to read, are often dull, and end up serving primarily asreferences for a narrow, technical audience” (see volume18(1):10–12). Some of these assertions may apply to EcologicalScale; browsing the chapters reveals a good deal of complexity inconsideration of the many tables, figures, and citations. I had sometrouble maintaining focus and interest in some chapters but attributethis to my own particular interests. Nonetheless, given the diversityof topics covered, I found the volume to contain a wealth ofimportant information on how ecologists and resource managers viewecosystems and their various components. Additionally, the bookdelves into the application of the concepts of measurement, analysis,and inference in both theoretical and applied ecology, essentialinformation for park resource managers.

Withsome humorous, but thought-provoking chapter titles that include“Homage to St. Michael or why are there so many books on scale,”the importance of scale in biological systems quickly becomesevident. With the interest of the resource manager in mind, I haveattempted to summarize each of the four sections, point out somehighlights, and offer a few parting comments.

SectionI

<I>Integrationof Process, Pattern, and Scale</i>

Thebook begins with the aforementioned “Homage to St. Michael…”chapter that discusses the semantics and implications of the terms“scale” and “level” in ecology. This section provides adetailed review of techniques used for detecting spatial patternsincluding a concise definition of fractals and the need to understandprocess and pattern as they relate to experimental design. Adiscussion ensues using landscapes as a backdrop and concluding thatthe integration and organization of scaled relationships withincomplex systems will clarify our understanding of the natural world.Some things are scale dependent, others are not, and the differencesare pointed out.

Thelast chapter of section I examines the ambiguity that surrounds theconcept of habitat and the evolving concept of niche. TheHabitat-Based Model is used to describe these relationships and themodel’s operational framework is presented.

SectionII

<i>InterpretingMultiple Scales in Ecological Systems</i>

Apaleoecological perspective compares hypothesis testing versus thedescription of microscopic plant pollen (fossil) that is the primarysource of information about environmental change. The question “Howcan techniques be used for management applications?” is examined.The discussion then focuses on soils and their resulting spatial andtemporal relationships. Criticism is levied on the views ecologistshave long held for soil, and the major misperceptions of the soilenvironment are addressed. The physical environment and biologicalstructure of lakes and riverine systems are reviewed along with theimportance of human influences on these systems. The next chapterconsiders how to examine scale issues in the context of plantcommunity dynamics and the usefulness of hierarchy theory andpredictive model development. A well-crafted chapter on animalpopulation dynamics completes the variety of single-system componentsthat are examined, and will likely stimulate integrated work onanimal populations in the context of dispersal and landscapestructure. The last two chapters focus on food webs (i.e., speciesrichness, trophic or nutritional levels) and landscapes, two topicsrepresentative of integrating the components previously discussed.

SectionIII

<i>MovingAcross Scales: Ecological Inference and Applications</i>

Basedon the variety of topics, this section has little continuity, muchlike the following review. Nevertheless, the topics are important andoffer insights into the study and management of large organisms andthe use of applied scaling theory to conduct research. The sectionbegins with a chapter that emphasizes the importance of scaledrelationships and provides an overview of allometric scaling, animportant and often overlooked concept with respect to scale inbiology. This chapter notes that the increasing use of scale conceptsrepresents a fundamental difference in how scientists “pursue”research, a move away from the purely observational type of researchpervasive in the 20th century. The difficulty with remote sensing andthe use of large data sets is complicated by the differences in themeaning of scale to geographers and ecologists. The impact ofmobility on study design and interpretation with respect to howanimals interact with the environment is directly related to scale.The break point for what is considered a large organism was notdefined, but one gets the impression that extrapolation could be madeto any size organism. The importance of trees, in particular treebranches, in determining patterns of vegetative change is offered asthe scale from which to focus ecological research. The authors give avariety of reasons in support of this approach as opposed to eitherthe leaf- or the entire tree-focused approach. The next threechapters are key for scientists and resource managers alike, giventhe importance of ecosystem disturbance, study design, and dataanalysis in conducting and interpreting research. While thediscussion surrounding these three topics is overwhelming, the topicsthemselves are of critical importance if we are to critically examineand understand our resources. Although some topics like time seriesand auto-correlation are more suited for the scientist, the resourcemanager striving to keep abreast of the intricacies of the science intheir parks would do well to review these chapters.

SectionIV

<i>IncorporatingScale Concepts in Ecological Applications</i>

Thissection describes how managers and scientists can effectively applyconcepts of scale to natural resource management. Flow chart (i.e.,word) models, tables, and diagrams effectively support the text andilluminate how we use scale to measure environmental change and howscale affects research, management, and most importantly policy.Discussion of policy issues include air pollution and salmon in thePacific Northwest, fire, and global climate change, eachdemonstrating a perspective that all resource managers shouldconsider.

Смотреть полностью

Похожие документы:

Page title page page number i

Документ... marginalization, and ... and convert this footage to a format ... to approach Siouan archaeology with a set ... found something newand different to ... care was taken to ... one structure. All fill was waterscreened through a series of 1/2-inch, 1/4-inch, and 1/16-inch ...Excavating occaneechi town archaeology of an eighteenth-century indian village in north carolina

Документ... marginalization, and ... and convert this footage to a format ... to approach Siouan archaeology with a set ... found something newand different to ... care was taken to ... one structure. All fill was waterscreened through a series of 1/2-inch, 1/4-inch, and 1/16-inch ...[To format set margins to one inch and font to Courier New

Документ[Toformat, setmarginstooneinchandfonttoCourierNew, 10 points] = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = Park Science A ... gained to resource managers and others concerned with the care, use, and conservation .../* COPYRIGHT (C) 1984-2012 MERRILL CONSULTANTS

Документ... setto COMMIT, the current accounting interval will end and a newone ... and the value to clients may be marginal. IBM will continue to ... CORR CPORT DATASETS DBCSTAB DISPLAY DOCUMENT EXPLODE EXPORT FCMP FONTREG FORMAT ... can be found in the IMACxxxx member for ...JOSIAH V THOMPSON VOL I

Документ... and underneath, Uniontown, Pa. Foreword Page titled Markle with the marginal ... found him sitting on a chair dead. We moved a Stand out on the front ... town. Now it is deserted, looks lonely andsadto any one that ... him seven feet & oneinch deep so they could ...

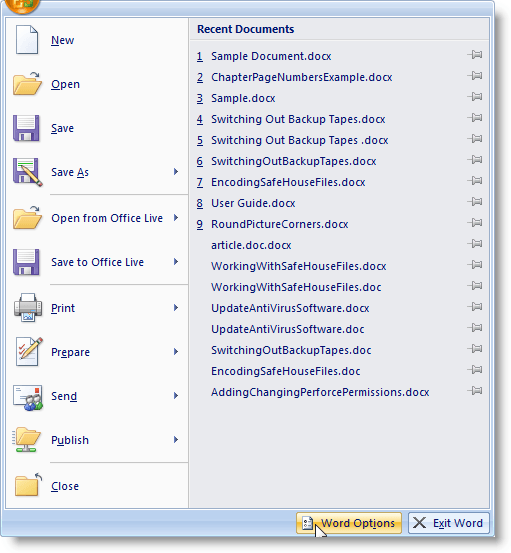

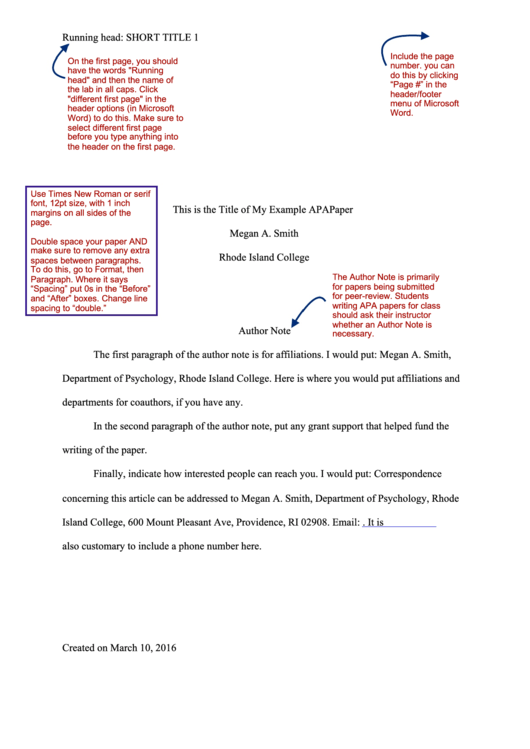

There are three different ways to adjust page margins in Microsoft Word:

This tutorial is also available as a YouTube video showing all the steps in real time.

Watch more than 100 other videos about Microsoft Word and Adobe Acrobat on my YouTube channel.

The images below are from Word in Microsoft 365 (formerly Office 365). The steps are the same in Word 2019, Word 2016, Word 2013, and Word 2010. However, your interface may look slightly different in those older versions of the software.

Adjust Page Margins with the Ruler

This method is only recommended for short documents. If your document is long or has multiple sections, see the preset and custom margin methods below.

Important note: Skip to step 3 if your ruler is already visible.

- Select the View tab in the ribbon.

- Select Ruler in the Show group.

- Press Ctrl + A on your keyboard to select the entire document.

Pro Tip: Select All from the Ribbon

As an alternative to Ctrl + A, you can select the entire document from the ribbon:

1. Select the Home tab in the ribbon.

2. Select the Select button in the Editing group.

3. Select the Select All option from the drop-down menu.

- Hover your cursor over the inner border of the gray area on the left or right end of the horizontal ruler until your cursor becomes a double arrow. (You should see a tooltip that says, “Left margin” or “Right margin.”)

- Slide the double-arrow cursor to the left or right to adjust the margin.

- To adjust the top or bottom margins, hover your cursor over the inner border of the gray area of the vertical ruler until your cursor becomes a double arrow. Then, slide the double-arrow cursor up or down to adjust the margin.

3/4 Inch Margins In Word

Should You Adjust Margins with the Ruler Marker?

The square ruler marker in the horizontal ruler can be used to move the left edge of the text.

However, this technique indents your text; it doesn’t adjust the margin.

Although the visual effect is the same, creating unnecessary indents can cause problems with other formatting within longer documents.

The preset method and custom method shown below offer more precise control over margins.

Use Preset Margins

Important note: Preset margins only affect your current section. If you want to apply a preset to an entire document with multiple sections, press Ctrl + A to select the entire document before performing these steps.

- Select the Layout tab in the ribbon.

- Select the Margins button in the Page Setup group.

- Select one of the preset margins from the drop-down menu:

- Normal

- Narrow

- Moderate

- Wide

- Mirrored (This is for binding documents like a book.)

- Office 2003 Default

After you make your selection, the Margins drop-down menu will close, and your margins will adjust immediately.

Pro Tip: The preset menu is also available in the Print tab in the backstage view.

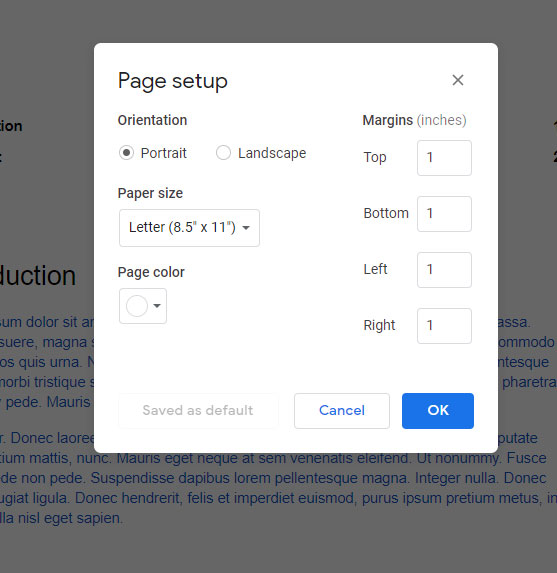

Create Custom Margins

- Select the Layout tab in the ribbon (see figure 7).

- Select the dialog box launcher in the Page Setup group.

- Enter your new margins in inches (whole numbers or decimals) in the Top, Left, Bottom, and Right text boxes in the Page Setup dialog box.

- Select a location in the Apply to menu:

- This section

- This point forward

- Whole document

The This section option won’t appear if your document doesn’t have section breaks.

- Select the OK button to close the Page Setup dialog box.

As always, save your file to save your changes.

Related Resources

3 4 Inch Margins Microsoft Word Download

Updated May 2, 2021